I Stared at One Painting for 3 Hours

My experience and other thoughts about attention after reading Stolen Focus, Four Thousand Weeks, and How to Do Nothing

I’m worried about my ability to pay attention.

I’ve read three books over the past several months that all seemed to touch on this anxiety, and that all complement each other.

And because of one of them I went to a museum and looked at one painting for three hours.

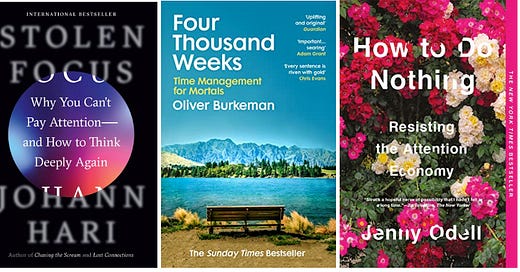

The books are (in the order I read them):

Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell

The “Stare at Art for three hours experiment” comes from Chapter 11 of Four Thousand Weeks:

“In a world geared for hurry, the capacity to resist the urge to hurry—to allow things to take the time they take—is a way to gain purchase on the world, to do the work that counts, and to derive satisfaction from the doing itself, instead of deferring all your fulfillment to the future. I first learned this lesson from Jennifer Roberts, who teaches art history at Harvard University. When you take a class with Roberts, your initial assignment is always the same, and it’s one that has been known to elicit yelps of horror from her students: choose a painting or sculpture in a local museum, then go and look at it for three hours straight. No checking email or social media; no quick runs to Starbucks. (She reluctantly concedes that bathroom breaks are allowed.)…. [Roberts] insists on the exercise lasting three hours precisely because she knows it’s a painfully long time, especially for anyone accustomed to a life of speed. She wants people to experience firsthand how strangely excruciating it is to be stuck in position, unable to force the pace, and why it’s so worthwhile to push past those feelings to what lies beyond.”

As I’ve been reading all of these books about attention, focus, and getting the most out of my life, I realized that this was an experiment I wanted to try. I’ve had a hard time processing and internalizing all of the lessons of these books, and I thought that taking some kind of concrete action might help spur some additional insights, or help make it “real” for me.

As if my inability to focus deeply isn’t real enough already…

So here is my account of the experience:

Preparation

3 hours already feels like a massive block of time for one activity but it’s actually worse. Between getting ready to leave the house, driving to and from the museum, parking, walking into the museum, and then walking around to actually select the piece that I will spend 3 hours with, we are actually talking about a 5 hour block of time to get this done.

Fatigue and hunger feel like they will be issues, because you can’t have snacks in the museum, but I also don’t want to eat a big meal right before I start.

Right off the bat I’m feeling overwhelmed, but I’ve committed to myself that I’m going to do this, so I pick a day, and decide to be at the museum by the time it opens at 11am.

Arriving at the Museum and Selection

I try to solve the hunger/fatigue issues by eating a protein bar and drinking an energy drink in the cafeteria before I wander around to select my painting.

My initial exploration reveals two hard truths: 1) it seems like the most exciting exhibits require an additional fee, and 2) I really need a painting or sculpture with a bench in front of it, because I am not going to survive three hours of standing in front of something.

The second truth actually becomes helpful, because instead of a whole museum of items to choose from, I really only have 10-20, which by virtue of the bench placement appear to represent a kind of curation of the best the museum has to offer anyway.

I decide I would rather spend time with a painting than a sculpture. I’m looking for something big and with lots of visual interest. I am worried about being very bored, so I want something that I think I can pick apart, or at least something with enough details that I can get lost in for some of the time.

These are the four paintings that I decided to choose from.

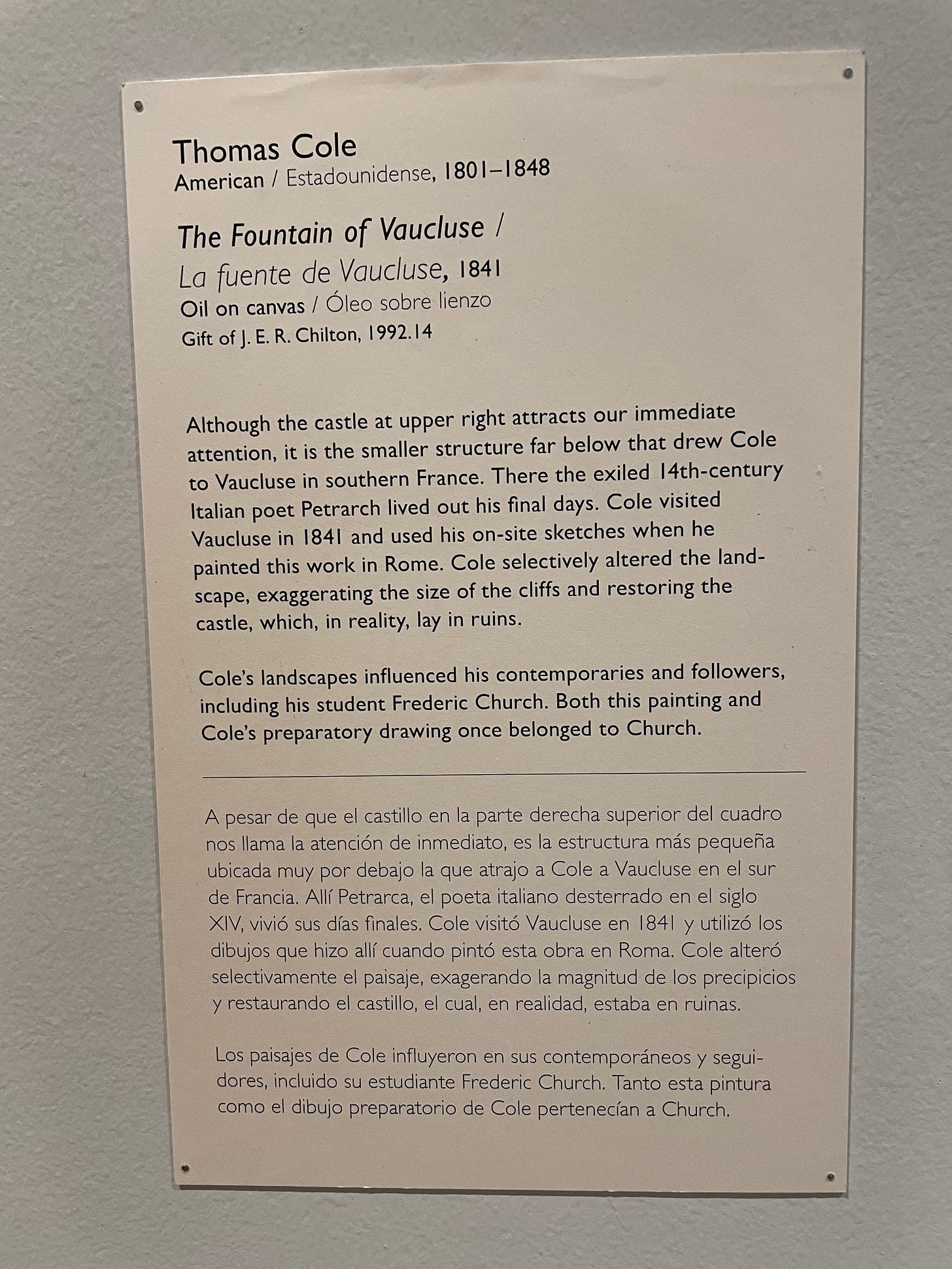

And this is the painting I chose, along with the description.

Start the clock!

My three hours began at 11:45am

Some stream of consciousness:

I am so tired. That energy drink didn’t do shit.

I want to look around at the other paintings nearby, mainly because I’m telling myself I can’t.

The “If I Were A Fish” song is playing in my head on repeat.

Am I experiencing this or just thinking of “takes”?

How long until I can look at my watch to see how much time has passed?

I thought this painting was mediterranean but it’s France. But it’s the south of France which is kind of mediterranean? Maybe?

Art as restoration - the big castle in the painting was rubble in real life, but the painter “restored” it for this depiction. But I didn’t get that insight from looking at it, I got it from reading the little plaque.

I have so many thoughts. My brain is very loud.

I wish I picked the big iceberg picture.

I Looked at my watch at 12:13pm. I’ve unlocked all of the mysteries of this painting already and it only took me 30 minutes!

What’s the difference between a stone and a mountain? Just size? Is there something else more significant?

What am I even supposed to be noticing or seeing?

I’m tired. I wish I could lay down on this bench and go to sleep.

I can force myself to sit in one place but I can’t force myself to pay attention, or forcibly improve the quality of my attention.

How am I contributing to this broken attention economy with the videos I make, the stuff that I write?

If I have to listen to another museum patron say the iceberg one is their favorite and so cool, I’m going to flip out. Of course I had to be “not like other girls” and pick this smaller one to be different.

Checked my watch again at 12:36pm. I have 2 hours and 9 minutes left. Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuu

I start thinking about how much surface area of the painting that the dark cloud would cover if you compressed all of the “dark cloud parts” into one rectangle. I try to divide up the painting and roughly visualize what fraction would be covered by cloud. My estimate is 1/12.

I have a lot of thoughts and observations about the painting itself but I’ll spare you.

I check my watch again at roughly the halfway mark. 1.5 hours left.

I check my phone once to make sure I don’t have a missed call from my son’s daycare or something.

I wish I had a way to objectively measure the quantity and quality of my attention.

I need to start meditating again. This struggle feels so much like meditation.

Time really slowing down after the halfway mark. Checked my watch with an hour and nineteen minutes left. Checked again an hour later, and somehow there is still an hour and ten minutes left.

I notice loud construction noises, and now I’m not sure how long they have been going on. Have they been doing this the whole time and I literally didn’t notice until now?

The noises stopped, so probably not.

Earlier I could lay on the bench and fall asleep. Now with 56 minutes and 28 seconds left, I am convinced I could lay down on the hardwood floor and pass out.

I have more thoughts about the painting itself.

I want to see an actual picture of this real life place but not sure if I’ll be able to find it.

I have therapy later today and am not sure how I will stay awake. More caffeine!

I took my only bathroom break with 38 minutes and 40 seconds to go. It took three minutes and I did not add that back onto my time.

I notice that the security guard that has been in my vicinity went to “my” painting while I was gone, presumably to see what is so damn interesting about this painting that anyone would look at it for this long.

I’m starting to think about Justified and Greta Gerwig.

As I again ponder my fatigue, I make a resolution to sleep 8 hours every single night no matter what (dear reader: I have not done that once since this experience).

I don’t know how to look at art.

Time’s up. I am not lingering. I am getting out of here.

Here are my core insights from the experience:

Spending the time allowed me to “see” this painting in a way I never would have otherwise

I am not trained to look at art. I actually used to paint a little when I was younger, but I don’t even think I took an art history course in college. But simply spending the time allowed this piece to open up for me in a way that it never would have if I just gave it a few casual glances while I was walking through the museum.

There were entire sections and details that I didn’t notice until after I had already been studying it for 30 minutes. This is what led to my initial “aha” moment of thinking I had “unlocked” the painting, and had uncovered everything there was to uncover about it.

At the same time I was aware that I was forcing it. I was trying to have a meaningful or emotional experience with a piece of art, instead of just showing up and experiencing it, and being with whatever came up. I was reminded again and again of my experiences meditating, and the problem of wanting to “force” a certain outcome or experience, as opposed to just being with the reality as it is. Observing reality as it is.

And the process of paying attention, noticing my attention had wandered, and then gently guiding my attention back to the painting, probably resembled meditation more than anything else.

I had an expectation or desire for some profound insight. Some deep epiphany that would be unlocked at the 2.5 hour mark, but that never really happened. I just sort of struggled through the entire time, and did my best to bring my attention back to the painting. To really see it. And I don’t know if I did it “right” or maybe the point is that there is no “right,” just the doing itself.

I do know that I ended up loving that painting.

The experience made me think about long books and movies in a completely different way

I don’t know if I ever watch a show or movie at home without looking at my phone at least once (just to check), and for certain shows I’ll find myself actively scrolling twitter while I listen to whatever it is in the background.

I also get intimidated by longer movies, for example the greatest movie of all time according to the critics in the 2022 Sight and Sound poll is Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles and it’s three hours and 21 minutes long. I’ve been scared to even attempt it because “oh no I will be so bored and won’t be able to pay attention.”

But after sitting in front of the same painting for three hours, no change, no nothing, how THRILLED I would have been to watch that movie in that moment. On a comfortable sofa. Maybe with snacks.

Every movie has at least 24 frames per second! This painting is just ONE FRAME. The same frame. And it doesn’t change.

It made me think about how we approach movies, books, and TV as entertainment rather than art. There’s an expectation that the burden is on the filmmaker to hold my attention, not on me to pay attention. It’s on them to dazzle me, entertain me, keep me hooked, and if my attention slips, my first instinct is to blame that movie. But that’s not how we approach art. We lean in. We expect to do the work.

I showed up and I didn’t expect the painting to do the work for me, I expected to bring my attention to it, and wanted to take whatever it had to give.

What if I could learn to approach films like that again? If I could lean in, and bring my attention to bear on the thing? What if I could start doing that more with these longer and more challenging books? What if I didn’t expect an author to “hook” me or pull me along, but I actively showed up and did my part?

This reminded me of an interview with Sune Lehmann from Stolen Focus. Lehmann, along with scientists across Europe, launched the largest scientific study about our collective attention, and during a conversation about the amount and speed of information we are all exposed to he said:

“What we are sacrificing is depth in all sorts of dimensions…. Depth takes time. And depth takes reflection. If you have to keep up with everything and send emails all the time, there’s no time to reach depth. Depth connected to your work in relationships also takes time. It takes energy. It takes long time spans. And it takes commitment. It takes attention, right? All of these things that require depth are suffering. It’s pulling us more and more up onto the surface.”1

I left the museum with a greater determination to try and show up in this way with some of the great films and books that intimidated me in the past.

We are fighting a losing battle when it comes to attention

One common point from each of the books I mentioned earlier is that this crisis of attention is not an individual problem but rather a systemic one. Hari in Stolen Focus describes that point this way:

“I found strong evidence that our collapsing ability to pay attention is not primarily a personal failing…. This is a systemic problem. The truth is that you are living in a system that is pouring acid on your attention every day, and then you are being told to blame yourself and to fiddle with your own habits while the world’s attention burns.”2 In fact, Hari even suggests that while we can try to tackle our attention issues individually, that will only get us so far, as one of the main takeaways of his book (which focuses on the larger forces behind the issue) is that “systemic problems require systemic solutions.”3

I also believe that our issues with attention are linked to our unwillingness to embrace finitude as described in Four Thousand Weeks. There is a societal imperative to “get it all done” which is impossible. We will never have enough time to do all of the things we feel are important. And yet, each of us has never ending to-do lists, and are constantly bombarded with stimuli competing for our limited life. These are complementary issues, if not exactly the same issue just presenting itself in different ways.

Burkeman in Four Thousand Weeks even objects to how we frame attention in our current culture:

“But to describe attention as a ‘resource’ is to subtly misconstrue its centrality in our lives. Most other resources on which we rely as individuals—such as food, money, and electricity—are things that facilitate life, and in some cases it’s possible to live without them, at least for a while. Attention, on the other hand, just is life: your experience of being alive consists of nothing other than the sum of everything to which you pay attention. At the end of your life, looking back, whatever compelled your attention from moment to moment is simply what your life will have been. So when you pay attention to something you don’t especially value, it’s not an exaggeration to say that you’re paying with your life.”4

Given all this, Burkeman notes that “the proper response to this situation, we’re often told today, is to render ourselves indistractible in the face of interruptions: to learn the secrets of ‘relentless focus’—usually involving meditation, web-blocking apps, expensive noise-canceling headphones, and more meditation—so as to win the attentional struggle once and for all. But this is a trap. When you aim for this degree of control over your attention, you’re making the mistake of addressing one truth about human limitation—your limited time, and the consequent need to use it well—by denying another truth about human limitation, which is that achieving total sovereignty over your attention is almost certainly impossible.”5

That’s why Johann Hari’s instinct was to escape the world and do a digital detox. This is an instinct that Jenny Odell describes at length in How to Do Nothing, brilliantly looking at the historical parallels of this drive to separate ourselves from the world (in times with fewer digital distractions I might add). She explores this tension thoroughly, and I resonate deeply with this passage describing a more realistic approach to this push and pull:

“Given the current reality of my digital environment, distance for me usually means things like going on a walk or even a trip, staying off the internet, or trying not to read the news for a while. But the problems is this: I can’t stay out there forever, neither physically nor mentally. As much as I might want to live in the woods where my phone doesn’t work, or shun newspapers with Michael Weiss at his cabin in the Catskills, or devote my life to contemplating potatoes in Epicurus’s garden, total renunciation would be a mistake. The story of the communes teaches me that there is no escaping the political fabric of the world (unless you’re Peter Thiel, in which case there’s always outer space). The world needs my participation more than ever. Again, it is not a question of whether, but how.”6

Reading these books and doing this experiment hasn’t been some magical fix to my struggles with attention. But I do feel a renewed determination to keep trying and showing up.

Thank you for reading. I would love to hear your thoughts about any of the above.

Page 33, Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Page 11, Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Page 12, Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Chapter 5, “The Watermelon Problem”, Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

Chapter 5, “The Watermelon Problem”, Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

Page 61, How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell

Michael, great piece (read it on Bite Size Reviews). As soon as I saw the four paintings, I said, Pick the castle, because it looked so intriguing, and so you did.

But I never would have suspected that some of the more interesting aspects of Cole’s painting is the information on the placard, things that can’t be learned from the painting itself (power of words vs. power of image).

For example, the rebuilt castle and enlarged cliff. Sometimes people carp about special effects and CGI-added mountains and castles in movies, yet here’s an example of “fine art” a couple centuries ago doing just that.

But perhaps the biggest surprise is the little castle where Petrarch lived. That’s the guy who the Petrarchan (Italian) sonnet is named for. If some English dudes hadn’t translated his sonnets, we might not have gotten the Shakespearean (English) sonnet. No more “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

That’s the guy, and he lived right there. Most of us are already familiar with a Petrarchan sonnet in English, Emma Lazarus’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” poem at the Statue of Liberty.

And many a sonnet about works of art have also been written. Perhaps the most famous (at least in German) would be Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” and its famous ending:

https://poemsintranslation.blogspot.com/2016/04/rilke-archaic-torso-of-apollo-from.html

Of course an art history prof would recommend a painting or sculpture, but you could do this exercise with non-art too, I would think. For example, observe a sleeping cat for three hours, watch its breathing, the little twitches, any sounds it makes, etc.

I loved this so much, and also realized I saw your TikTok of this without realizing, which made reading your afterthoughts incredibly interesting, and even though you were bored, it makes me want to try this as well. I find myself routinely in the scolding-myself-for-not-focusing camp, and I've been trying to purposely do less things simultaneously, which has helped. Like just enjoying folding my laundry in silence rather than cramming in audiobooks or trying to clean the whole room at the same time. I like applying the idea to art. Great great essay, Michael!